Europe’s strategic focus on a vast hydrogen pipeline network has come at the expense of necessary power grid reinforcements, leading to significant inefficiencies in its decarbonization efforts. Despite a rapid increase in renewable energy capacity, a lack of transmission infrastructure has forced the curtailment of billions of kilowatt-hours of clean electricity. By prioritizing speculative hydrogen markets over direct electrification, policymakers risk inflating system costs and slowing the transition. Experts now point to the proactive grid-first strategies of China and India as superior models for integrating renewable power and ensuring long-term energy security.

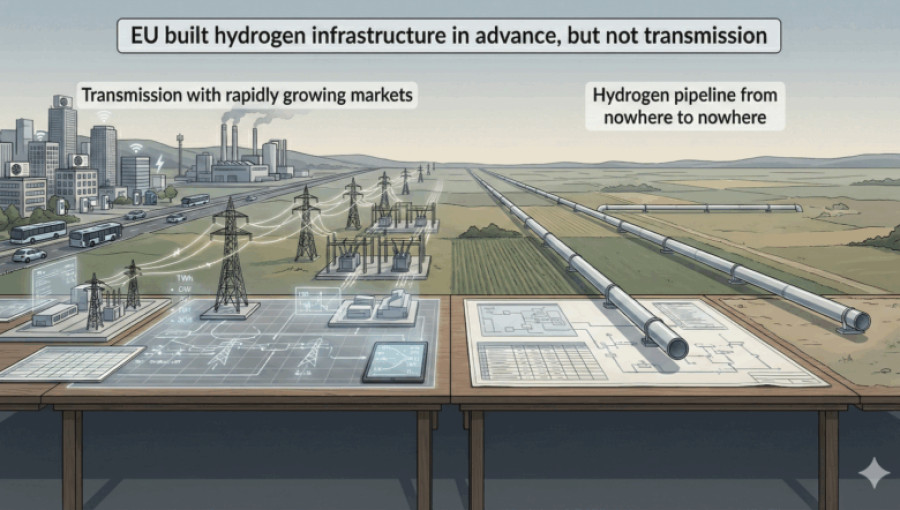

The European energy transition is currently grappling with a “pipeline to nowhere”—a 400-kilometer segment of a proposed hydrogen backbone that currently lacks both suppliers and consumers. This infrastructure project highlights a broader policy failure: the prioritization of technological aspiration over the practical realities of energy demand. While Europe has long understood that the electrification of transport, buildings, and industry would drive electricity demand up by 40% to 70% by 2050, the physical grid required to move this power has not kept pace.

In Germany, renewable energy generation expanded far quicker than the transmission lines needed to carry it. Onshore wind capacity jumped from 27 GW in 2010 to over 60 GW by the early 2020s, but major corridors intended to move power from the windy north to industrial centers in the south were delayed by over a decade. This bottleneck resulted in the curtailment of more than 6 TWh of renewable electricity in a single year. This wasted energy, already funded through subsidies, could have displaced fossil fuels but was instead discarded because the grid reached its physical limits.

This lack of transmission capacity has created a false narrative of “surplus” electricity, which proponents use to justify large-scale hydrogen electrolysis. However, analysts argue that building electrolyzers in grid-constrained regions does not solve the underlying problem; it merely adds a load that competes with direct electrification. In contrast, China and India have adopted a “grid-first” approach. China has constructed more than 40,000 kilometers of ultra-high-voltage transmission lines to connect remote wind and solar farms to urban hubs, successfully reducing curtailment rates to low single digits even as capacity continues to soar.

The economic argument for a hydrogen-heavy economy also faces steep challenges. Green hydrogen currently costs between $8 and $12 per kilogram, making it uncompetitive against fossil-derived hydrogen at $1 to $2 per kilogram or direct electrification. Furthermore, the physics of hydrogen are inherently inefficient. Delivering one unit of useful energy via hydrogen requires up to 3.5 times more electricity at the source compared to direct electrification, which loses very little energy during transmission and use.

The opportunity cost of this strategy is significant. The proposed European hydrogen backbone is estimated to cost nearly $100 billion. Experts suggest that the same investment in grid reinforcement and distribution upgrades could unlock hundreds of gigawatts of renewable capacity and support millions of electric vehicles and heat pumps. Unlike hydrogen pipelines, which require entirely new markets to emerge, electricity transmission serves a universal and growing market from the moment it is activated.

Ultimately, the lesson for policymakers is one of sequencing. To achieve efficient decarbonization, the priority must be expanding the power grid to eliminate waste, followed by the direct electrification of cost-effective sectors like heating and transport. Hydrogen should be treated not as a universal energy carrier, but as a specialized tool reserved for niche industrial feedstocks where no electrical alternative exists. Following evidence-based demand rather than speculative infrastructure goals will be essential for a cost-effective transition.