Sodium-ion batteries are emerging as a potential alternative to lithium-ion technology, offering enhanced safety and a more stable supply chain. However, they currently face significant hurdles in energy density and manufacturing costs. While raw materials like sodium carbonate are inexpensive, the lack of industrial scale makes sodium-ion systems roughly 30% costlier than their lithium counterparts. With lithium-ion technology continuing to advance rapidly in performance and price, sodium-ion is expected to remain a niche solution for specific energy storage and automotive applications rather than a broad market disruptor.

While the basic architecture of sodium-ion batteries mirrors that of lithium-ion systems—utilizing electrodes, electrolytes, and separators—the physical properties of sodium present inherent challenges. Sodium particles are larger than lithium, which inevitably results in heavier and more voluminous battery packs. Although round-trip efficiencies remain competitive at over 90%, the lower power density of sodium-ion remains a primary drawback for high-performance applications.

Recent product launches highlight this performance gap. Hithium recently introduced a 162 Ah sodium-ion cell designed for a one-hour battery energy storage system (BESS), claiming a lifespan of 20,000 cycles. While intended to manage load spikes in data centers, the company has not yet provided the specific power density data required for a full technical assessment. Similarly, CATL and HiNa have introduced cells with energy densities ranging from 165 to 175 Wh/kg. While these figures approach average lithium iron phosphate (LFP) levels, they still lag behind cutting-edge LFP batteries, which now reach 205 Wh/kg and offer significantly faster charging rates.

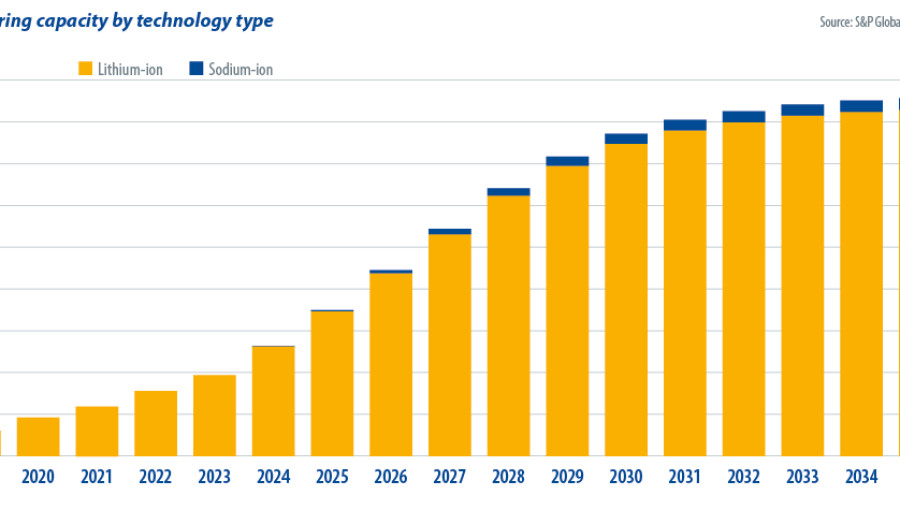

The economic landscape further complicates the adoption of sodium-ion technology. Despite the use of affordable materials—such as sodium carbonate, which costs hundreds of dollars per metric ton compared to the thousands required for lithium carbonate—manufacturing costs remain high. Sodium-ion production also utilizes aluminum current collectors instead of more expensive copper, yet without the economies of scale enjoyed by the lithium-ion industry, these savings have not yet translated to the consumer. Currently, sodium-ion demand is nearly non-existent, with only 148 MWh of installations recorded globally.

The disparity in energy density is most evident in large-scale storage solutions. For example, BYD’s lithium-ion-powered MC Cube system provides 6.4 MWh of capacity within a 6.1-meter equivalent container size. In contrast, a sodium-ion version of the same system yields only 2.3 MWh. This significant difference in volumetric density makes sodium-ion less attractive for projects where space is a premium, even before considering its current price disadvantage.

Nevertheless, sodium-ion offers distinct advantages in safety and logistics. These batteries are far less susceptible to thermal runaway, reducing the risk of fire and explosion. They also perform better in extreme temperatures and provide a strategic alternative to the lithium supply chain. Since sodium can be sourced or synthesized globally, it protects manufacturers from the price volatility and geographical concentration associated with lithium mining.

Ultimately, the future of sodium-ion depends on its ability to move beyond niche applications, such as starter batteries for vehicles or storage in extreme climates. While lithium-ion continues to dominate the market through massive research investment and rapid scaling, sodium-ion could eventually secure a permanent role if it can successfully bridge the current gap in cost and density through increased production volume.